The evolution of America’s trade policy in the past century

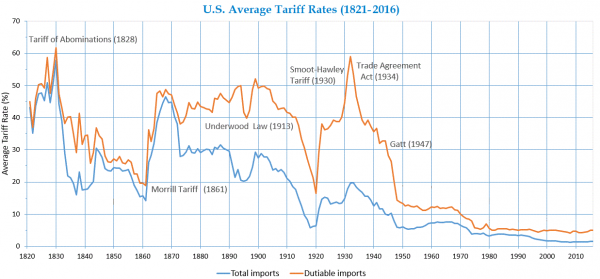

Since the end of the 19th century, namely after 1860, the US adopted an aggressive, protectionist stance regarding international trade.1 Average tariff rates rose, in a single decade, from roughly 15% to 45% (Figure 1). This period of persistent high tariffs coincided with the affirmation of America as a serious player in the international panorama.2 Slowly but steadily, tariffs where diminished throughout the beginning of the 20th century. They reach a relative minimum after the Great War and rise again during La belle époque. The increase is pushed even further after the Great Depression of 1929.

After 1935, the path is a clear one: especially after the 2nd World War, tariffs kept on decreasing. The US were now activists of the Free-Trade world order and worked around the clock – whether it be via GATT/WTO3, regional trading blocs4 (NAFTA) or by multilateral agreements5 –to low tariffs to near-zero values. Thus, it is clear that periods with low tariffs sometimes coincide with periods of spectacular growth2, but sometimes protectionism coincides with it as well6. It is often argued that, after the 2nd world war, the international community was more in favor of such a policy due to the scars left by the war.

Nevertheless, there are other economic factors which should be also taken into account, namely economic interdependency.7 Furthermore, as H.Prechel argues, “Business unity among domestic capitalist groups was highest (…) undermined accumulation in the economy as a whole. (…) business was less unified during periods of rapid economic growth”8 Moreover, as some authors argue, “no one sector has been dominant in the postwar United States”9. Another extremely important factor, frequently disregarded when analyzing tariffs, is that non-tariff trade barriers actually increased substantially during the post-2nd world war until the end of the century10.

The Consequences of Trumpism in trade

Mr. Trump is a gambler. With every controversial statement, angry tweet or campaign-style speech, he aims at pursuing his agenda in a unique fashion. He deliberately acts as an incumbent alpha male, imposing its power via coercive means11. He does so to pursue “America’s national interests”. “It is going to be America first” he often says. And he does so regarding migration, enforcement of the law, environmental issues, international trade agreements, and many other areas.

His approach is superbly risky, and many do not grasp the skill to handle or understand it. In no way do I endorse Mr. Trump’s behavior. Nevertheless, it is remarkable the success he had so far, with so many faux pas along the way. The list is vast: Mr. Trump often labels as fake news many Media brands (namely CNN); “Witch Hunt” is a constant when referring to the investigation on Russia’s interference on the American elections; he acts as a dictator within his own party; denies global warming, ignoring abundant evidence… The list could go on. What should be kept in mind, though, is the permanent bully behavior. And he uses it a lot in international diplomacy.

Consequences in the short term are already visible: punctual disruptions of international trade12, a broad increase in tariffs by and against the U.S., and occasionally a more hostile exchanging of words. I would dare to say it is the natural reaction of a declining nation. Not that the US will collapse, but rather that it is bound to lose its supremacy. And this premise leads me to assess that the short-term effects differ a lot from the medium-term ones. By being aggressive in the global panorama, Trump aims at delaying the loss of the front-runner place to China and, later, second-best to India13. It is a rather individual move of a country and not a broader one.

Besides the U.S., no other major country is advocating protectionism. In opposition, Europe14, and even China15 are championing the fight for free-trade. Thus, the ongoing discussion on whether free trade will lose ground to protectionism is, in the medium term, exaggerated. Furthermore, Mr. Trump defends a political agenda which is not ideological, but rather pragmatic16: he aims at pleasing those who elected him. He does not care for protectionism or free-trade. As long as he can bring back home a victory (even if a pseudo one), he will label it as “free but fair trade17”. And those who support him will cheer. Moreover, it must be kept in mind that, being a democracy, the US shifts its economic strategy often. And Trump is the symbol of an exception – not a trend – regarding trade policy. Both the Democrats18 and the Republicans (namely the moderates19 and the extreme Tea Party20) majorly advocate for free-trade. And with no substantial benefits arising with protectionism, they will continue to do so.

A purely temporary setback

The revisionism which Trump supports, as if someone obliged the U.S. to sign free-trade deals, advocates that the current drawing of trade partnerships is profoundly unjust for America21. This unfairness may have risen due to the lack of previous policymakers’ competence, or by the shifting in economic strategies and circumstances. It may not even be a realistic premise at all. But whether this is true or not, realpolitik – “politics or diplomacy based primarily on considerations of given circumstances and factors, rather than explicit ideological notions or moral and ethical premises”22 – will prevail.

America’s power – namely how much it trades with its partners – is too meaningful (economic-wise) for third countries to enter in an ad aeternum economic war with the U.S. Besides the circumstantial “tit for tat” retaliations, it is clear most will allow Trump to come back home with small, yet symbolic victories, so as to sustain their own growth, as I have explained in my previous answer.

When looking at the TTP, the case may be a little different from this narrative at a first glance, but it is not. The United States retreat was indeed symbolic. Being an agreement with numerous but far away nations, its economic effects would have been mild (when compared to NAFTA, for example)23. Although net benefits would have been positive to all signatories24, Trump pulled out, arguing it would cost American jobs and a higher current account deficit25. But it is false that free-trade gave a step back. In fact, the remaining signatories enforced a new trade deal which emulates TPP, but without the US (called CPATP)26. Therefore, free-trade ended up giving a small but steady step towards a more trade-liberalized Pacific.

As for NAFTA 2.0., to rip apart the original free-trade agreement with no substitute would have dire consequences. The volume of American exports and imports from Canada and Mexico is huge and having no backup plan would cause chaos27. As argued before, a symbolic victory was all Donald wanted in order to fulfill the government’s pledges. Namely, by granting a bigger access to its dairy market (Canada), and implementing bigger tax exemptions to domestic car manufacturers (in all 3 countries)28, the deadlock was broken: as of October 1st, 2018, the USMCA was born29. Consequently, NAFTA was kept alive, no major trade disruptions took place, and the Americans could chant “victory”.

Lastly, the most complicated scenario is certainly China. Albeit economic disruption is big, so are the stakes. Whereas both Canada and Mexico are highly dependent but traditional economic partners, China is not.5 Trump often claims China has already an ongoing economic war with America, whether it be due to currency manipulation30 or buying huge amounts of American sovereign debt. Moreover, both aim for global supremacy, via international relations and military power. This state of affairs, although politically feasible on the short-run (with the exacerbations of nationalisms), has its days numbered31. With prices skyrocketing and the scarcity of Chinese and American products, populations (namely in the US, which has democratic means of reaching power) will demand a policy change. Furthermore, having an isolated international stance regarding trade, the US will lack backup from its allies. In a camouflaged way, the US will be forced to change their tone31. That moment will certainly set history in motion, symbolically marking the definitive end of an US-hegemonic era and the return to a bipolarized one.

Bibliography

- The Economist. A historian on the myths of American trade. Econ. 2017:1. https://www.economist.com/books-and-arts/2017/11/23/a-historian-on-the-myths-of-american-trade.

- Irwin DA. Clashing over Commerce: A History of US Trade Policy. 1st ed. Washington D.C.; 2017.

- Destler I. America’s Uneasy History with Free Trade. Harv Bus Rev. 2016. https://hbr.org/2016/04/americas-uneasy-history-with-free-trade.

- Office of the United States Trade Representative. North American Free-Trade Agreement. Free Trade Agreements. https://ustr.gov/issue-areas/industry-manufacturing/industrial-tariffs/free-trade-agreements#North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). Accessed October 3, 2018.

- Council on Foreign Relations. U.S. Relations With China. Council on Foreign Relations. https://www.cfr.org/timeline/us-relations-china. Published 2018. Accessed October 3, 2018.

- Chang H-J. Kicking Away the Ladder: The “Real History of Free Trade.”; 2003. https://ips-dc.org/kicking_away_the_ladder_the_real_history_of_free_trade/.

- Milner H. Resisting the protectionist temptation: Industry and the making of trade policy in France and the United States during the 1970s. Int Organ. 1987;41(4):639-665. doi:10.1017/S0020818300027636

- Prechel H. Steel and the State: Industry Politics and Business Policy Formation, 1940-1989. Am Sociol Rev. 1990;55(5):648. doi:10.2307/2095862

- Kurth JR. The Political Consequences of the Product Cycle: Industrial History and Political Outcomes. Vol 33.; 1979. doi:10.1017/S0020818300000643

- Salvatore D. Import penetration, exchange rates, and protectionism in the United States. J Policy Model. 1987;9(1):125-141. doi:10.1016/0161-8938(87)90006-8

- Landler M. Trump Takes More Aggressive Stance With U.S. Friends and Foes in Asia. New York TImes. 2017.

- Bryan B. Trump’s shift on a massive deal is the latest example of his confounding trade policy. Bus Insid. 2018. https://www.businessinsider.com/trump-tpp-shift-trade-war-tariff-policy-confusion-2018-4.

- PWC. The World in 2050.; 2016. https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/issues/economy/the-world-in-2050.html.

- Burchard H Von Der. Germany: free trade’s reluctant champion. Politico Europe. 2017.

- Elliott L, Wearden G. Xi Jinping signals China will champion free trade if Trump builds barriers. The Guardian2. 2017.

- Eggen D, Farnam TW. Trump’s donation history shows Democratic favoritism. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/trumps-donation-history-shows-democratic-favoritism/2011/04/25/AFDUddtE_story.html?noredirect=on&utm_term=.138f4d518cd2. Published 2011.

- Stanford J. Is Trump right about free trade or is there a fair alternative? The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/mar/19/is-trump-right-about-free-trade-or-is-there-a-fair-alternative. Published 2018.

- Price K. Obama’s Strange New Love of Free Trade. Huffington Post. https://www.huffingtonpost.com/kevin-price/obamas-strange-new-love-o_b_7649760. Published 2015.

- Council on Foreign Relations. Campaign 2016: John Kasich. Council on Foreign Relations. https://www.cfr.org/interactives/campaign2016/john-kasich/on-trade. Published 2016.

- DePillis L. On free trade, tea partyers and the left want the same thing. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2015/03/06/on-free-trade-tea-partyers-and-the-left-want-the-same-thing/?utm_term=.1422161542a4. Published 2015.

- Gittleson K. US Trade: Is Trump right about the deficit. British Broadcasting Corporation. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-43336599. Published 2018.

- Humphreys ARC. RealPolitik. In: Wiley-Blackwell, ed. The Encyclopedia of Political Thought. Wiley-Blackwell; 2014. http://www.academia.edu/4100553/Realpolitik.

- Petri PA, Plummer MG. The Economic Effects of the TPP. Peterson Inst Int Econ. 2016;104. https://piie.com/publications/chapters_preview/7137/01iie7137.pdf.

- United States International Trade Comission. Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement: Likely Impact on the U.S. Economy and on Specific Industry Sectors. Washington D.C.; 2016. https://www.usitc.gov/publications/332/pub4607.pdf.

- British Broadcasting Corporation. Trump executive order pulls out of TPP trade deal. Br Broadcast Corp. 2017. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-38721056.

- Ming C. Global trade just had a “one step forward, one step back” day. Consumer News and Business Channel. https://www.cnbc.com/2018/03/09/tpp-11-countries-sign-trade-agreement-as-trump-implements-tariffs.html. Published 2018.

- Statista. North American Free Trade Agreement – Statistics & Facts. Statista. https://www.statista.com/topics/3464/north-american-free-trade-agreement/. Published 2018. Accessed October 4, 2018.

- Cable News Network. US and Canada reach deal on NAFTA after talks go down to the wire. Cable News Network. https://edition.cnn.com/2018/09/30/politics/trump-nafta-canada/index.html. Published 2018.

- Schlesinger JM, Mackrael K, Salama V. U.S. and Canada reach NAFTA Deal. The Wall Street Journal. 2018.

- British Broadcasting Corporation. Trump accuses China of “manipulating” its currency. British Broadcasting Corporation2. https://www.bbc.com/news/business-45251091. Published 2018.

- Schweller R. Opposite but compatible nationalisms: A neoclassical realist approach to the future of US-China relations. Chinese J Int Polit. 2018;11(1):23-48. doi:10.1093/cjip/poy003